Housing in Japan has a long and varied history. We can distinguish between traditional forms of architecture and more modern forms.

The most common type of residence in Japan today is the detached home.

Multi-unit buildings are also very common.

An interesting feature of Japanese housing is that dwellings are intended to be torn down and rebuilt relatively quickly.

This characteristic may be associated with the country’s climate and environment.

Japan is a land of frequent earthquakes and typhoons. The climate can also vary considerably across the archipelago. There are severe winters in the north and humid summers in the south. Rainfall can also be high.

Japanese dwellings have had to withstand the elements. With these environmental challenges, damage to housing was common. As a result, houses are often built with early replacement in mind.

The lifespan of a home with a wooden structure is generally considered to be around twenty years.

For houses made of reinforced concrete, it is between twenty and thirty years.

Homes in Japan (as opposed to the land itself) are viewed as depreciating goods rather than as appreciating investments. So, often, the value of the dwelling itself will go down each year while the value of the land may go up.

Partial home renovation is not as common in Japan as it is in other OECD countries.

Within Japan millions of dwellings are unoccupied.

There is a mix of occupier-ownership and renting. Rental rates are higher in urban areas due, in part, to the expensive cost of land in these areas.

Occupier-ownership is higher in rural areas.

In the 1980s, new homes in Japan cost around 5 to 8 times the average annual income.

Loans in Japan are often for 20 years with a 35% deposit as opposed to the US where loans are often spread over a longer time period of thirty years and require a lower deposit.

Unoccupied dwellings are known as akiya.

There is also a category of dwellings called jikko bukken which are associated with murders, suicides and similar events.

Another kind of housing in Japan is company housing (known as shitaku). In the 2000s, there were over a million dwellings of this type in Japan. They often accommodate young company workers for their first few years after joining a company.

Let’s look at some come common features of modern Japanese houses.

The genkan is a quintessential feature of Japanese homes. It is the entry to the house where one can remove one’s shoes. The initial level is the same level as the ground outside and then one steps up into the house.

Multi-purpose rooms. Besides the kitchen and bathrooms, the other rooms of a dwelling often aren’t set aside for a specific purpose. These general-living rooms can be used as family spaces or for study or for work depending on what the occupants choose to do at any one time. Much Japanese furniture is portable, so the use of rooms is flexible and can be changed relatively quickly.

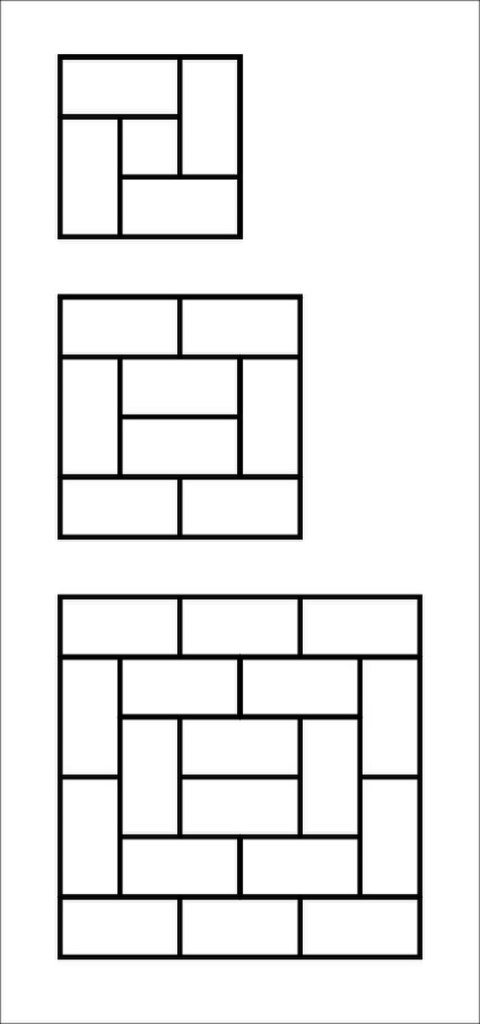

Fusuma and shoji. Many Japanese homes feature removable panels or screens – fusuma or shoji. Shoji are more translucent than fusuma. These removable panels allow for the varied partitioning of the entire house. Rooms can me made larger or smaller.

Tatami. Tatami are traditional straw mats. One tatami can usually accommodate a person lying down. A room with six tatami would be a regular size.

Rooms in Japan are either western-style or Japanese-style. The Japanese-style is known as washitsu. Washitsu rooms will have a tatami flooring.

Some historical influences

Early on in Japan’s history, the kitchen was separate to the main building in order to keep smoke and the risk of fire separate from the rest of the house.

During the Kamakura period (1185-1333) the kitchen increasingly moved into the main house and by the Edo period the kitchen was integrated into the house.

The use of a common well by multiple households was still widespread.

Some homes had bamboo pipes that brought water into the house.

A big issue in earlier centuries has been the spread of fire. This was particularly a concern in urban areas where there were many houses in a small space.

In the Edo period, houses were constructed mostly of wood. After some large fire events, the authorities would mandate ‘fire barrier zones’ or hiyokechi and ‘wide alleys’ or hirokouji.

After 1601, the Shogunate ordered that thatched roofs had to be replaced by shingles.

The authorities went back and forth on the use of tiled roofs.

After the Meireki fire in 1657 (where over 100,000 people lost their lives), many tiles had fallen on residents and caused many injuries and so the authorities went back to requiring the use of shingles after 1661.

Tokugawa Yoshimune came to power in 1716. During his reign, the regulations were changed again and people went back to using tiles.

While in many ways Japan displays aspects of western modernity, there are still many quintessentially Japanese designs and values represented in modern Japanese homes.

Leave a comment