The Tōkaidō was one of the grand, old roads of premodern Japan.

It connected the two major cities of Edo (now Tokyo) and Kyoto. Edo was the center of government while Kyoto was the home of the Japanese Emperor and court.

Most who traveled the Tōkaidō did so on foot.

There weren’t many carts on the road. This may have been due to the damage that could occur to the path from a thin wheel width – especially in poor weather.

While cargo was carried on the path, much was sent ahead by boat along the coast.

High-class individuals would be carried along the path in palanquins or ‘norimono‘.

The Tōkaidō was a crucial form of communication. It was also a key piece of nation-building. For a long time, there had been constant warfare in Japan. The three great unifiers – Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu steadily subdued the various provinces and began to stitch together the nation we now know as Japan.

The third of these unifiers – Ieyasu – instituted the Sankin–kōtai system whereby domain lords would have to regularly travel to Edo and report to the Shogun. This ate up the valuable time and finances of the various lords and decreased the chance that they would scheme and revolt against the Shogunate.

There were 53 stations spread out along the Tōkaidō. These post stations or ‘shukuba‘ had stables for horses and food for travelers.

Traveling permits were required to pass the checkpoints.

There were numerous rivers along the route that needed to be crossed.

There were ‘runners’ posted at stations who could rush Imperial messages along the route at great speed.

The route was 514 kilometers in length along the southern coast of Honshū. Accordingly, the distance between posts was 9 to 10 kilometers.

Assuming that a decent walking rate is 3 kilometers per hour it should have been relatively straightforward for a single traveler to reach the following post in a morning or an afternoon. This also assumes that the route was in good condition due to dry weather. It seems possible that a determined traveler could do two or three stations in day. However, we should expect the pace to be reduced if they were carrying a heavy load or if there was inclement weather like rain or snow. There may have also been queues of people at river crossings waiting for ferryman to take them to the other side. There may have also been delays at post stations due to the inspection of permits.

The route of Ieyasu’s time is very different today. The starting point at Nihonbashi has a highway running over the top of it. The southern coast of Honshū today is very urbanised. The old path often intersects with main roads and highways. Today the whole route could be comfortably traversed in three weeks.

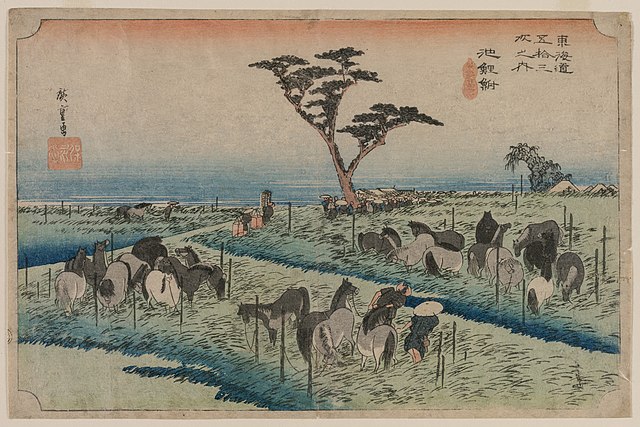

The route was immortalised by the artist Hiroshige in his series of woodblock prints entitled ‘the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō or in Japanese, the 東海道五十三次, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi. Hiroshige first traveled the Tōkaidō in 1832. His prints were extremely successful. They could be purchased by everyday people. In Hiroshige’s prints one can see the Japan of the time – porters carrying heavy loads and ferrymen taking travelers across rivers. There are picturesque fishing villages and ornate bridges. There are women in kimonos and houses with steeply-sloping roofs. Mountains raise up steeply – exaggerated for his audience. Horses feature frequently in Hiroshige’s prints. There are palanquins, Shinto gates and stone lanterns along the path. One can see the raised paths that helped travelers negotiate the wet, low-lying land. Curiously, Hiroshige depicts the Tōkaidō in different seasons. It is unlikely that he experienced the sunny landscapes and snow-covered ground in the same trip. One would think that creative license has been taken again for the sake of his audience. He brings humans and landscapes together – indeed the people are framed by the landscape. There are sand bars in the rivers and a kite is used to convey the movement of the wind. One gets the sense of starting in an urban environment (Edo) and then traveling further and further into the countryside. Encountering bridges become less frequent. As one gets close to Kyoto the process reverses and we feel that we are getting closer to the scene of human activity.

Japanese provinces have changed over time. in Ieyasu’s time, the 53 stations were spread across 10 provinces. Today, they are spread across 7 although the vast majority are located in just 5. Today, the prefecture with greatest number of stations is Shizuoka (with 22).

The Tōkaidō was a crucial route in the development of Japan. It helped the Shogun to maintain control over the country and control over the Emperor and court. Contact between different domains increased and it was an important contributor towards the growth of early Japanese nationalism.

Leave a comment