By the feudal period farmers were not an undifferentiated mass in Japan. Hierarchies were in place even at this time. At the top of the pyramid were myoushu (名主 ). These were prominent farmers who held a status higher than regular farmers.

In the 1500s there was an increase in agricultural productivity.

The use of money as a means of exchange was becoming more widespread.

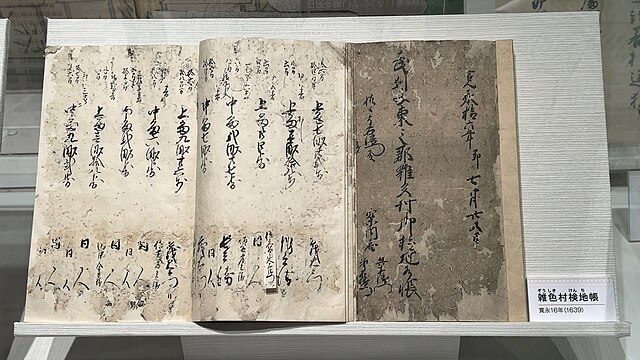

During the 1590s a lot of effort was put into conducting land surveys. The Taikou Survey (太閤検地 – taikou kenchi) was the famous land survey of the age. A new unit of measurement (the chain) was adopted. Individual plots were carefully measured and their owners were identified. The Shogun’s state apparatus needed taxes in order to function. These land surveys were critical instruments for extracting taxes from the various parts of Japan.

Using money as the basis of exchange existed for a time but the system changed to using bales of rice or ‘koku’. This may seem strange from a modern viewpoint. The bean counters in the central treasury found that the value of money had a wider degree of fluctuation than rice production. Rice production was relatively stable. Farmers worked a similar number of hours for a similar number of days, year after year. Yes, there could be some variation due to weather events or crop failure but rice output was seen to be more stable than money.

There were different units for counting rice. There were bales of rice – (俵 – hyou) and a ‘rations’ unit (扶持 – fuchi). Another translation for fuchi might be stipend. These stipends could be paid to Samurai in return for their services or to other kinds of retainers.

The Tokugawa Period

The ‘Four Occupations’ are well-known to students of Japanese history. The Shi-nō-kō-shō system (士農工商) placed individuals into four general occupations. One was either a Samurai, a farmer, an artisan or a trader. Interestingly, the position of a farmer was above that of a trader. Farmers produced the food that everyone relied upon. The work of the Samurai, artisan or trader was not possible without the food supplied by farmers. Traders were at the bottom of the social ladder because they didn’t produce anything tangible. They simply made a living buying items that others had produced and sold it at a higher price.

It is a very different system to today isn’t it? Some of the most highly sought after jobs today are in finance, banking, share trading or stockbroking. These are highly-paid jobs. People engaged in these jobs often enjoy high status. Many people look up to them and want to emulate them.

In the Tokugawa era around 85% of the population was engaged in agriculture (p. 111 of Jansen – see source at the end of the article).

Earlier in Japanese history it had been possible to be a part-time farmer and a part-time soldier.

Now there were sharper divisions. Tokugawa culture didn’t like ambiguity. Social mobility became exceptionally difficult, if not impossible.

The produce tax ( 年貢 – nengu) sustained the system. Nengu might also be translated as ‘land tax’ or ‘annual tribute’.

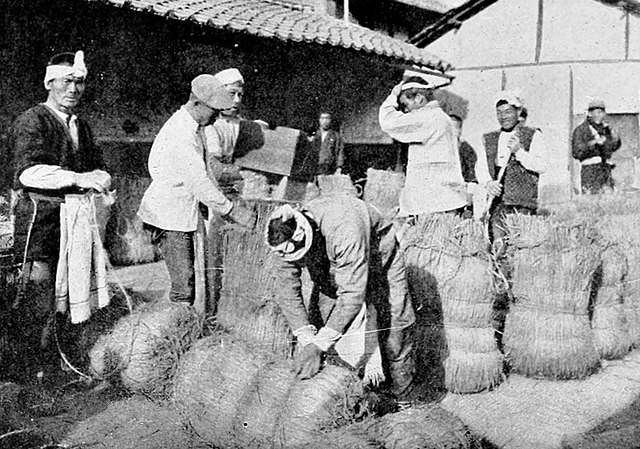

In Tokugawa Japan the basic unit of society was the village. The community was all-important. Rice planting was done as a communal effort. The head of the village was often hereditary.

It was not unusual for farmers to have a number of plots separated by some distance. The benefit of this was that they farmers didn’t have all of their eggs in one basket. If one plot became flooded or too dry then farmers could often rely on another plot. The downside was that a huge amount of productive time was lost through travel between plots.

Some farmers owned their land. However there were also landless farmers – (水飲み – mizunomi – or ‘water drinkers’).

Japan’s population was growing rapidly during the Tokugawa era – perhaps by a factor of three.

Domains covered Japan. Famine could periodically come to a domain. Because domains had a history of non-cooperation with each other it often proved very difficult to have food brought in from other domains in the event of famine.

There was no industrial revolution in Tokugawa Japan but it has been said that there was a ‘industrious revolution’ (p. 228).

Crop failure could be a serious matter. In the 1830s there was a series of crop failures. 1833, 1836 and 1837 were all critical years.

The Meiji Period (1968 onward)

The years from 1867 to 1869 also saw crops fail.

As the Tokugawa was state was weakening and on the verge of breaking down social regulations relaxed somewhat.

From 1871 Samurai and common people could marry each other.

Around this time farmers were required to take on surnames. As a result, many contemporary family names have associations with farming life. Examples include 中農 (nakanou – ‘center of farming’) and 鋤柄 – (sukigara – ‘plow handle’).

Around this time the basic unit of Japanese society shifted from the village to the family.

A new land system was instituted in which 3% of the value of the land had to be paid in money.

The Twentieth Century

In the interwar years there was much conflict between landlords and tenants (p. 566).

By 1949 the proportion of farmers who owned their own land had increased to 88.9% (p. 683).

Despite the scale of agricultural production inside of Japan the population was large enough to make self-sufficiency impossible and some foodstuffs needed to be imported.

There was a boom in agricultural technology. Artificial fertilisers were used more often. Crop yields increased. Many farmers adopted mechanisation. Machines were used to sow crops and to harvest them.

Agriculture has changed over time in Japan. However perennial issues are access to land, the ownership of land, the status of farmers compared to other occupations and the level of taxation. Marrying supply and demand together has never been perfectly. Even in the summer of 2024 there was a brief shortage of rice. However this a far cry from the threat of famine in centuries gone by. The ability of the government to ensure the efficient distribution of food to different parts of the country is much better these days.

Source: Marius B. Jansen – The Making of Modern Japan

Leave a comment