Sado Island

Sado is well known for its precious mineral deposits – particularly gold and silver.

Sado forms part if Niigata Prefecture.

The Tsurushi Silver Mine (鶴子銀山) was discovered in 1542 and the Nishimikawa Placer Gold Mine (西三川砂金山) followed in 1593.

As a placer gold mine, those working at Nishimikawa used traditional methods to separate the gold from sand in the alluvial deposits.

In 1601 Sado became a territory of the Shogun and in the same year gold was discovered at Kinpokusan (金北山). The island of Sado is made up of two mountain chains running parallel to each other with a central plain between them.

Another famous mine on the island is Doyu no warito (道遊の割戸). This mine was open-cut. As miners dug downwards from the top of the mountain they created a distinctive V shape. Mining at Doyu no warito was active from the 1600s to the Meiji period.

The peak of gold production on Sado was in the early 1600s (around 400 kilograms annually).

Gold and silver made its way to Edo in order to be minted. Gold went to Kinza (金座) – in present-day Nihonbashi.

Silver also made its way Edo but the silver mint was located in a different area – in Ginza (銀座). This part of the city has kept its name right up to today.

Prior to the 1600s, coins circulating in Japan had come mainly from China.

It was Tokugawa Ieyasu who was largely responsible for the standardisation of coinage in Japan.

By the latter half of the 17th century many of the precious minerals that were easy to access had been mined on Sado. They now became harder to reach. One way of dealing with the issue was to use forced labour.

Sado has a history as a dumping ground for individuals who were exiled or banished from the mainland. The island’s distance from the mainland made it ideal for this purpose. In this way, Japan’s criminal punishment system intersected with Sado’s mining operations.

Mining on Sado prior to the Meiji Period was a low-technology affair. Mining was not mechanised. Mining and refining was done by hand.

It is important to remember that Japan at this time was in a period of self-enforced seclusion and isolated from much of the world.

The use of gunpowder and other explosives was not present on Sado at this time.

Parallel tunnels were dug for ventilation.

Unlike in Europe, there were no steam engines to help pump water out of shafts.

Mining shafts traveled horizontally. It was not until the Meiji Period that vertical shafts were sunk.

Villages on Sado were integrated with mining. Mining was the focus of community life. If we assume a new generation every 25 years, from 1600 to around 1875 there would have been 11 generations living in close proximity to the mines with villagers making their living from traditional mining and honing their methods. Mining infused local culture.

Despite the use of relatively low-level mining technology, the gold produced at Sado was highly refined.

The precious metals produced at Sado buttressed the new financial system of the Shogunate and was also crucial in facilitating later trade with other countries.

Nishimikawa Gold Mine ceased operation in 1872.

The Meiji Period brought in western engineers and western technology. New drilling equipment was introduced.

In 1877 the first vertical shafts were sunk on Sado.

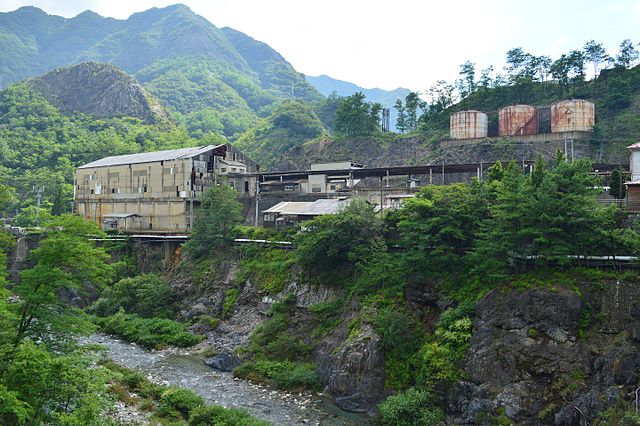

As part of the introduction of western mining techniques and facilities a flotation plant was constructed at Kitazawa. The plant relied on German know-how.

In the late 1800s ownership of the Sado mines shifted from the Shogunate to the Meiji government and then on to Mitsubishi in 1896.

Electricity was introduced to the mines on Sado.

Sado mines increased their production and in 1940 produced around 1,500 kilograms of gold and 25 tons of silver.

Tsurushi Ginzan ceased its operations in 1946.

The Aikawa Mine (相川金銀山) closed in 1989.

Sado has around 400 kilometers of mines snaking their way beneath the ground.

According to Korea, many Koreans were forced to work on Sado to produce metal during the second World War.

This became an issue when Japan was trying to get the mines of Sado registered on the World Heritage List. There was scarce reference to the Koreans at the former mines sites on Sado. Korea was pushing for more recognition.

Iwami Ginzan (石見銀山) – Silver

Iwami Ginzan is located in Shimane Prefecture on the main island of Honshu.

It was the largest silver mine in Japan and was mined for around 400 years (1526-1923).

A special ash-blowing method (灰吹法) was utilised at Iwami Ginzan.

In the 16th century Japan produced around one third of all silver in the world.

Peak production at the mine was in the early 1600s with an output of roughly 38 tons per year.

Silver from this mine was used to produce coins which were used in East Asian trade. Iwami silver was regarded as being of very high quality.

Following the Battle of Sekigahara in (1600) the mine transferred into Tokugawa hands.

By the nineteenth century Iwami was in decline and closed in 1923.

Copper – Ashio Copper Mine

From the 1600s copper was being mined at Ashio (足尾銅山) in present-day Tochigi Prefecture.

Copper was found at Ashio around 1550 but mining didn’t commence until an official license was awarded in 1610.

The mine was owned by the Shogunate.

Some of the copper was exported outside of Japan and some was used to produce coins for circulation within Japan.

At the peak of the mine’s production around 1,200 tones of copper was being produced every year.

In 1871 ownership changed into private hands. There was another change of ownership in 1877.

Output rose to some 2286 tons by 1884.

By-products created in the mining process were arsenic trioxide and sulfuric acid.

This mine was the source of Japan’s first large pollution event in the 1880s. This incident was crucial in the formation of the environmental movement within Japan.

Pollution from the mine was being carried downriver.

By the 1870s the colour of the Watarase River was changing. Fish were dying and accordingly, the livelihood of fishermen was under threat.

Deforestation was also taking place. Wood from the surrounding forests was being used to prop up mine shafts and for fuel in the copper smelting process.

With less trees, flooding became a more serious problem.

In 1907 the miners at Ashio rioted. They were seeking better pay and conditions. The police arrested hundreds of miners and over a hundred would face charges. All miners were fired following the incident and went through a process of vetting before being rehired. This demonstrated the relative lack of power of the miners and the relative strength of mine owners.

The mining of precious metals in Japan really took off from the 1600s. Methods were basic but they continued for hundreds of years and generations of miners managed to produce very refined gold and silver.

The mining of these precious metals was essential for the new economic system of the Shogunate. It allowed new coins to be created and this aided the unification of Japan.

There were some changes to production during the Meiji Restoration. One of the reasons that mining was able to last hundreds of years in Japan was due to the low level of mechanisation. Simply put, it took workers a long time to extract a little. If mining had began in Meiji times rather than Tokugawa times the industry would have had a much shorter shelf-life.

Compared to many other countries, Japan’s gold, silver and copper mineral reserves were relatively small. In the twentieth century it would become cheaper to import these resources from other countries.

The story of gold, silver and copper mining in Japan is not only a story about resource exploitation. It is also a story about workmanship, generations of families passing on their specialised techniques and it is also a story about Tokugawa power.

Leave a comment