Rail in Namibia has a history of over a hundred years.

Most of the network was built when the territory was under German control.

During this time the area was known as German South West Africa.

Railway construction took off in 1897 with a line running from Swakopmund to Windhoek and this was completed in 1902.

A private company, Otavi Mining and Railroad (O.M.E.G), laid a line from Swakopmund to Otavi and then on to Tsumeb between 1903 and 1906.

A line branching off from Otavi and going to Grootfontein was laid in 1907/1908.

The Namibian rail network links to two Atlantic ports – Walvis Bay and Lüderitz.

In 1915 South Africa took over control of the territory and South West Africa became connected to the South African rail network.

After independence control of Namibia’s rail network was managed by TransNamib. Nambia has a gauge size of 3 feet, 6 inches over the most of the country.

In 2002 a major international conference was held in South Africa which discussed how to connect the various railway networks in Southern Africa. This conference formed part of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD).

One obvious project would be a link to Zambia. The most obvious option would be to extend a line from Grootfontein traveling north-east into Zambia.

Namibia already connects to South Africa (from Karasburg in the south) to Upington across the border.

Another obvious project would be to link Namibia to Angola in the north. The obvious crossing point on the Namibian side would be at Oshikango.

Another project that has been talked about for a long time is a line from Namibia to Botswana. The obvious option here would be to extend a line eastwards from Gobabis in central Namibia, across the border and continue eastwards to link up to Botswana’s rail network. Part of the difficulty with this project is that Botswana’s network is not spread evenly throughout the country. It is concentrated in the far east and links with South Africa and Zimbabwe. There is no pre-existing line in the west or even center of the country. Therefore the proposed Trans-Kalahari line would require much more track to be laid in Botswana than in Namibia.

Angola

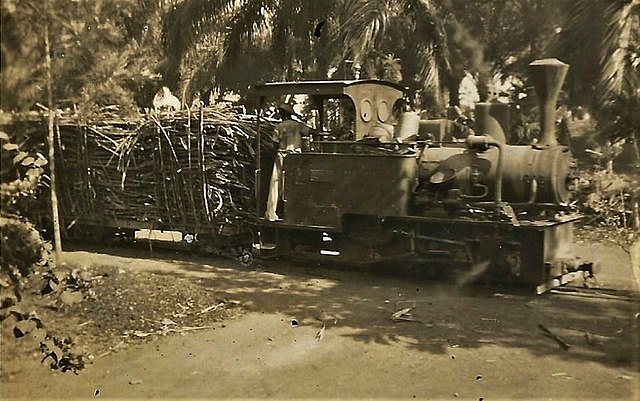

One of the main critique’s of European colonialism in Africa is that infrastructure was used as a way to extract wealth from colonies rather than for the benefit of the people. If one was looking for shining example of this one may want to look at the rail system in Angola.

Angola has three main rail lines – one in the north, one in the center of the country and one in the south. Crucially, these lines do not intersect with one another. They seem to be a way to quickly and efficiently penetrate into the colony (as it was at the time under the Portuguese) and move goods quickly to the nearest port for shipment to Portugal.

The northern-most line runs from Luanda (on the Atlantic coast) to Malanje.

The central line runs from Lobito right across the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The central line connects with the Katanga line in the DRC. The first train went through in 2013. The DRC has its own infrastructure problems. The Katanga region is one of the wealthiest in the Congo due to its mineral wealth. The government of Congo received most of it’s revenue from the proceeds of minerals mined in Katanga. The administration in Kinshasa well knew that this region would be crucial for providing funds for the development of the entire country. Katangan leaders were vocal in arguing for the the area’s wealth to be kept in the region in order to benefit the local people. Katanga actually split off from the Congo in 1960 but was reintegrated just a few years later. At the time the, Congo received about a third of its revenue from the sale of Katangan copper.

The major parts of the DRC are perhaps less connected than they were in the colonial period. The post-independence period has been marked by regional rivalries, war and conflict. There has never been enough investment for the infrastructure needs on the country. But it has been particularly pronounced since independence. The Congo’s dictator – Mobutu – had a habit of starving rival regions of funding.

There is also the simple fact that the DRC is a very challenging environment in which to build and maintain infrastructure. The DRC sits on the equator. Much of the country is rainforest. Rainfall is high which can turn roads to mud.

The DRC has an interest in seeing a dependable rail line traveling through Angola but it has many challenges in maintaining the line on its side of the border.

The southern-most line in Mozambique stretches from Moçâmedes to Menogue.

Construction on Angola’s rail lines began in 1887. The Luanda line opened in 1889. The Moçâmedes line followed in 1910 and the central Banguela line opened in 1912. Some additions continued to 1961.

The speed at which these lines were built was quite astounding. It stands in stark contrast to the difficulty an independent Angola has had in maintaining and extending the system post-1975. Angolan rail lines certainly went backwards in the first few decades after independence. The main cause was the civil war the raged across the country until 2002. Rail lines acted as a double-edged sword during the civil war. They can be used to quickly move your own troops around the country but they can also be used by rival groups. Much of the lines were destroyed.

So, the overall picture looked like this: the Portuguese built the lines very quickly but to take advantage of Angola’s resources rather than to stitch together a nation that would be stable once the Portuguese were gone. Much of the network was destroyed and Angolans are now in a process of getting back to where they were prior to the civil war with hopes to extend the network and finally connect to other African states. It is tragic that the onset of independence coincided with the destruction of infrastructure. It is amazing to think that half a century on from 1975, Angola still isn’t connected by rail to Namibia.

China has been a crucial partner in the post-war reconstruction of Angola’s railways.

One positive feature is that most lines are narrow gauge with a width of 3 feet, six inches. This is a blessing. The Namibian network has the same gauge and this will make interconnection so much easier.

Possible extensions to the Angolan network

The Caminho de Ferro do Congo.

This proposal has been talked about seriously since 2010. This would see a line extending north from Luanda, crossing the border with the DRC. It would then travel around 40 kilometers through the DRC to the Angolan excalve of Cabinda. It would then continue northwards reaching Congo (Brazzaville) for a total length of about 950 kilometers. If built, it would be the wild ride of the west. It would cross a border of one kind or another four times. It will difficult to get agreement over the exact route and to finalise cost-sharing, network management issues and revenue matters. Not to mention the fact that Angola faces an armed insurgency in Cabinda whose members do not accept that the territory and mineral wealth belong to Angola.

A link with Zambia should be more straight forward. It would make sense for it to branch off from the Benguela line and travel south-east for around 300 kilometers.

In terms of linking with Namibia, the obvious thing would be to branch off the southern line (perhaps near Capelongo) and extend a line south for around 340 kilometers to cross the border close to Onjiva or Namacunde on the Angolan side. This proposal has been seriously talked about since the late 2000s but the realisation of line is still a long way off.

When Angola’s leaders in Luanda look around at neighbouring countries they will see problems everywhere. To the south, Namibia is relatively stable but what resources does Namibia have that Angola can benefit from via a rail connection? Angola and Namibia both have ports and so don’t require a rail link to access the sea.

Zambia is much more integrated with transport networks to its south and east. The reason for this is partly historical and partly geographical. There would be some benefit in an Angola-Zambia link but it remains to be seen how large this benefit will be and how much trade will develop.

There is much greater instability to the north. The DRC has been proven to be very unstable over time. There is the strange situation with Cabinda – part of Angola but sort of out there on its own and surrounded by another country.

Namibia and Angola both face uphill battles in expanding their rail networks. Due to Namibia’s history as a territory controlled by South Africa it has historically looked southwards when it comes to rail. The country has wanted to expand for decades now but has had limited financial resources and other priorities to address at the same time.

Angola’s experience as a Portuguese colony has left it isolated from its neighbours. As the three main domestic lines don’t connect, Angola is even isolated from itself. This is doubly the case when one considers that there no rail line to Cabinda.

Extending the networks in both countries makes absolute sense but it is much more difficult to say exactly when and how these changes will take place.

Leave a comment