Since World War II, Sovereign Wealth Funds have spread like wildfire around the world.

Up to that point, the finances of most countries was managed like this:

Gather up the yearly taxes, pays the expenses for the year and if there is more money spent than taken in, just mark it down as a deficit in the ledger. Repeat.

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) begin with a certain amount of seeding capital. This capital grows and the profits can be used to help cover the cost of a specific area of government expenditure. It might be to provide for an aging society. It might be to pay for the cost of health care. It might be to help cover disability payments. It might be to fund the retirement benefits of public servants.

Not all countries have sovereign wealth funds. But there are some patterns. If a nation has significant mineral resources, it is much more likely to have a sovereign wealth fund. Many oil producing countries have one and many of these can be found in the Middle East.

Oil is finite resource and it will run out one day. Some oil producing states in the Middle East have precious little else that they can sell to the rest of the world. Therefore, it makes sense to put aside some of the wealth derived from oil and quarantine it so that its value is not drawn down. Future generations can then use the profits for their own well-being.

Norway

The Government Pension Fund Global of Norway is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. Its seed money came from Norwegian oil and gas revenue. Hydrocarbon resources were developed in Norway in the 1970s. The fund was set up in 1990 and now holds over US $1.7 trillion in assets. This wealth translates into roughly $325,000 per citizen.

The fund invests in financial markets outside of Norway. This a way of diversifying risk away from the Norwegian economy.

The price of oil can fluctuate a lot. The fund allows the government to transform oil revenues into a more stable asset.

Norway has a relatively small population – just over 5 million people. The country has scored a trifecta – control of a valuable resource, wise economic management in creating the fund decades before the oil ran out and a small population to provide for.

The Norwegian government is permitted to take out up to 3% of the fund’s value each year.

It holds more European shares than any other entity.

As such a significant holder of European shares, it can have a huge influence on markets. If it chooses to be actively involved in the governance of the firms in which it has invested, it potentially has a lot of weight to throw around. It could vote in favour or against company policies and directions at Annual General Meetings. It could pursue more activist interventions if it so chose. For example, it could focus on business ethics, corporate governance and environmental concerns.

Some Norwegians question whether money should be continue to be placed in the fund or whether it is better spent now. There will always be things for governments to spend money on. There are always issues to address. This is the now / later debate. Should they spend now or squirrel revenue away? One is reminded of the fable ‘the cricket and the ant’. The cricket spends his autumn relaxing and enjoying himself while the ant works away diligently, storing his food for the winter.

There are debates around the type of companies the fund should invest in. Some argue that fossil fuel companies should be out. There is some irony in this given the initial seed capital of the fund comes from the sale of a fossil fuel. Some argue that there should be no investment in companies that make military weapons. Some say there should be no investment in coal mining.

Kiribati

The Pacific nation of Kiribati is an interesting case. The SWF there is named the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund and has over $1.5 billion in assets.

The population is only 133,000. So the value of the fund translates into around $11,000 per person.

The fund was set up in 1956 – relatively early by world standards.

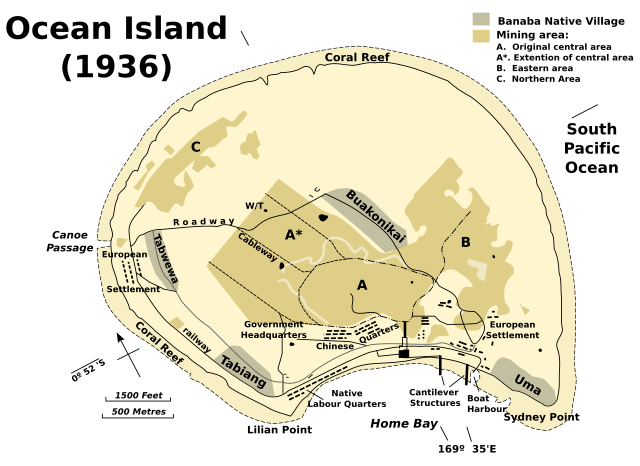

At the time, Kiribati was dependent on the sale of phosphate. In the 1950s phosphate revenue made up roughly half of all government revenue.

Phosphate mining ended in 1979 and at the time accounted for 80% of government earnings.

Since then, Kiribati has been much more dependent on foreign assistance. The government also brings in money by granting fishing licenses – some $30 million per year.

Remittances are also important for the people of Kiribati with those working outside the country sending money back home to support family members.

Tourism also is of great importance to the economy.

As most food is imported, exchange rates and the cost of basic items is a real issue.

In 2009 the EU gave Kiribati $9 million and the UN development program gave $3.7 million. However, Australia was the largest donor. This is unsurprising given that Australia is the closest large, developed country and has a long history in the Pacific. Australia also has key security interests in the region.

Japan also provided $2 million and Taiwan 10 million.

Kuwait Investment Authority

Set up in 1953, the Kuwait Investment Authority is the oldest SWF in the world.

As of 2024 it had around US $ 1 billion in assets.

In the mid 1980s the KIA was investing heavily in the United Kingdom.

The Ministry of Finance has a seat on the board as does the Energy Minister and the Governor of the Central Bank.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund (PIF) is one of the largest SWF in the world with an estimated value of US $930 billion.

Created in 1971, it is a rather opaque institution.

In 2022 it made a 1.5 billion investment in Credit Suisse. This made the Saudi National Bank the largest shareholder. Nevertheless, it was still less than 10% of the total shares of the company.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has been Chairman of the PIF since 2015.

In contrast to many other SWFs, the majority of investment takes place within Saudi Arabia itself.

Still, the fund has invested in the Premier League and Newcastle United.

The PIF is a funding vehicle for ‘Vision 2030’ – the Saudi strategy for diversifying its economy away from oil.

The PIF has taken out a 5% stake in Uber as well as a 5% stake in gaming company Capcom.

In 2020 it took out a minority stake in Boeing, Meta and Citigroup. In each of these companies, the PIF held more than half a billion dollars worth of shares.

The PIF even owns part of Disney and Bank of America.

In 2019 it announced that it would be investing heavily in the production of solar panels within Saudi Arabia.

The assassination of Jamal Khashoggi has had an affect on the fund. Many companies that had been planning on working closely with the PIF announced that that they would no longer proceed.

In 2022 the PIF took out a 5% stake in Nintendo. Gaming is big business and it is clear that Saudi Arabia wants a slice of the pie. New titles are coming out every year. The target market of this industry is relatively young and the industry is booming.

The following year a 10% stake was acquired in Heathrow Airport.

Some critics allege that the government of Saudi Arabia is using the PIF for ‘sportswashing’ – funding major sporting events in order to draw attention away from the more repressive aspects of the regime such as women’s rights and the deaths of foreign workers on major construction projects.

This kind of criticism has been aimed at LIV golf tournaments. When LIV was created, it entered into direct competition with the PGA. For a long time the PGA was the premier Golf association. The PGA had the history. It had the allure. But LIV had deep pockets and was prepared to fork out astronomical sums in order to bring top players to the league.

Qatar

The Qatar Investment Authority was set up in 2005.

By 2024 it held over half a trillion dollars in assets.

Some say that the Authority lacks transparency.

Like many other SWFs in the Gulf States, its creation was only made possible due a windfall from mineral resources.

Most of its money is invested outside of Qatar.

When it does invest inside the country, it tries to do so in sectors other than energy in order to drive diversification.

Similar to Saudi Arabia, the Qataris also have a ‘Vision 2030’ plan.

The Authority is keen to invest in countries like the UK and France.

In 2008 it took out a 12.7% stake in Barclays. it also took out a stake in the UK’s largest supermarket chain – Sainsbury’s.

In 2010 the Authority bought a 6% stake in Credit Suisse and by 2023 the Qatari fund was the second largest shareholder.

In 2012, Qatar Sports Investments finalised the purchase of the Paris Saint-Germain Football Club.

In the same year it acquired a 12% stake in Royal Dutch Shell.

The Qatari fund also holds a 20% stake in Heathrow Airport, proving that this is a popular asset for Gulf State SWFs.

Massive investment by SWFs into major companies and critical infrastructure of foreign countries raises important security concerns. What will happen if government relations break down? What if there is a trade war? Could an SMF decide to halt the operations of a major supermarket chain in another country, for example? Could a SWF interfere in operations at Heathrow Airport – one of the busiest terminals in the world?

Much depends on the degree of governmental control over the SMF. Some funds are more independent than others. It will also depend on the relevant laws of the host country. Laws may allow for foreign investment but still ensure that infrastructure cannot be leveraged in the event of friction or conflict. Many countries have some kind of foreign review board that examines the sale of companies and how they affect national security. They will often block a sale if they think it is too much of a risk.

Since then end of the Second World War there has been a large growth in SWFs. This has been a response to revenue windfalls and an attempt to deal with government expenditure that can seen coming down the track. Globalisation is continuing apace. Economic interdependence knits sovereign countries together. But massive investment in the companies of other nations raises issues of national security and potential economic manipulation.

Leave a comment