In WWI Belgium decided to remain neutral. Its colony, the Belgian Congo followed suit.

But Germany had plans for both territories.

Germany invaded Belgium and just eleven days later the Congo was also attacked.

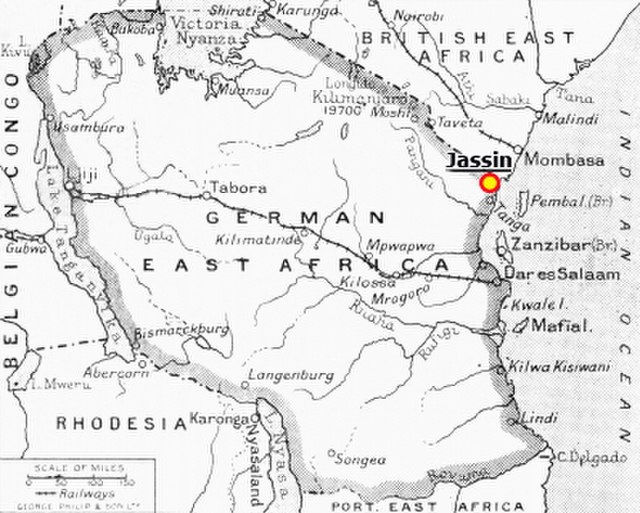

The attack came from the east – the German colony in East Africa.

The two colonies were separated by the massive Lake Tanganyika. There were no tanks. The first skirmish came in the form of a steamboat. The Germans opened fire on a cafe on the western side of the lake, came ashore and severed several telephone lines.

The plan was to attack important strategic sites rather than capture entire regions.

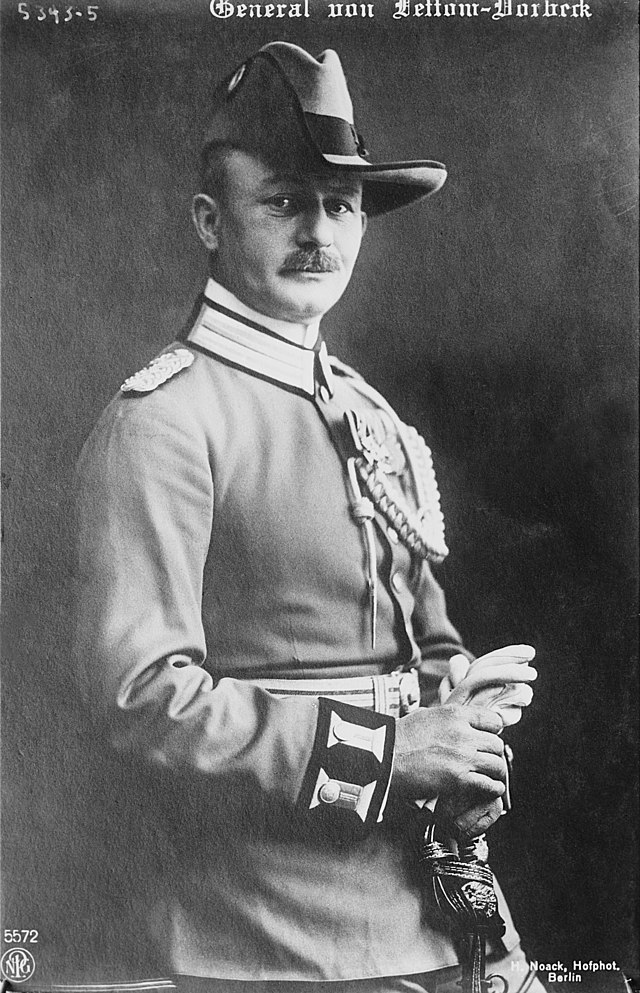

The number of troops in German East Africa was relatively small. According to David Van Reybrouck, General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck had some 3000 German soldiers and 11,000 Africans at his disposal.1

Congo fared much better than Belgium would during the war. While Belgium was overrun, the Congo was left relatively untouched.

From 1915, the Germans tried again and again to capture the territory of Kivu. They were ultimately unable to achieve their goal, but they were able to take control of both Lake Tanganyika and Lake Kivu.

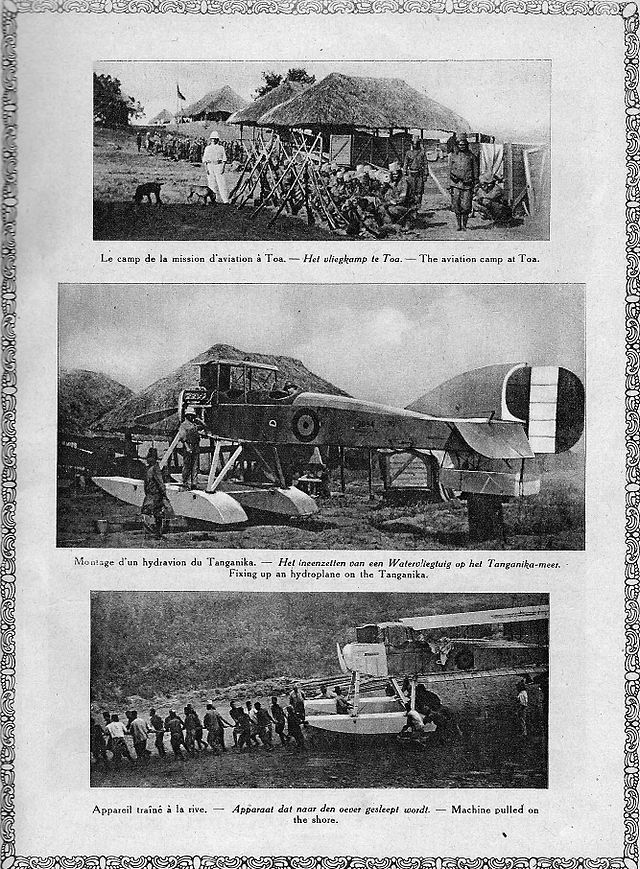

Aircraft were not numerous in the colonies of Africa at this time. Lake Tanganyika was so large that the chop on the water’s surface made it difficult for seaplanes to take off or land.

David Van Reybrouck has suggested that there were probably 7 African porters for every soldier and that 260,000 of them would have been active in WWI.2 He also writes that 25,000 may have died during the war.3

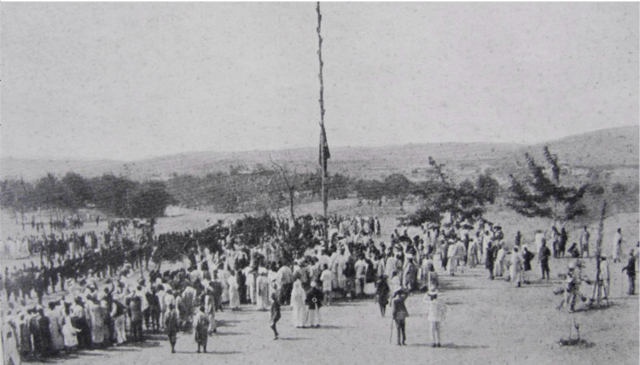

By 1916, Congolese forces had entered German territory, taking Kigali (in present-day Rwanda). They continued on to Tabora. By taking this administrative capital of German East Africa, Congolese troops controlled around a third of the German colony.

The Germans in East Africa continued fighting throughout the entire war, surrendering only in 1918.

If Germany had succeeded in taking control of Congo, it would have connected German East Africa with German South West Africa. A strip of German Territory would have run from one side of the African continent to the other.

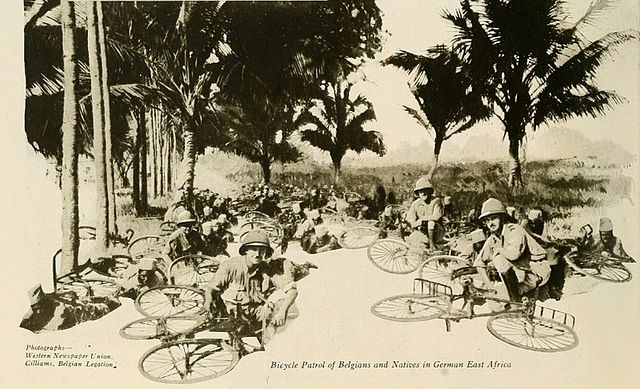

Another German objective was to divert the attention and resources of the Allied forces in Europe towards Africa. It could be argued that the Germans were somewhat successful in this. The British, Belgians and Portuguese all expended energy in trying to counter German ambitions in Africa. Tens of thousands of Africans were involved in hunting down Lettow-Vorbeck and his little band of soldiers.

The Germans would attack Allied posts, hoping to draw a response. If engaged, they would retreat back into their vast territory.

In a sense, the Germans engaged in defensive warfare rather than offensive warfare.

In the end, it was Belgium that profited from the war. Belgium picked up the new territories of Uranda and Urundi.

After the war, Germans tended to view Lettow-Vorbeck and his troops as resolute fighters. They were seen as brave men holding out for the entire war against larger and more powerful forces. He was David while the Allied forces were Goliath. Although hostilities had concluded with German surrender, it was sometimes suggested that the German leader and his men remained undefeated.

During the war, many died from disease rather than injury sustained in battle and the majority were African porters.

Porters were sometimes paid, sometimes not.

The African battles of WWI are not as well known as those fought in Europe.

Many more Africans than Europeans died in these African battles, which tended to be hit-and-run skirmishes and guerilla warfare rather than set piece engagements.

Leave a comment