Out of Nara Buddhism (710-794 CE), new forms began to take shape.

The court apparatus regulated monks.

The regulation of monks was formally managed by a government office called the Sōgō (僧綱), or Bureau of Monastic Affairs.

This office controlled the ordination, ranking, and discipline of monks and nuns. It also supervised temples.

This was part of the broader effort to centralise control over religion and align Buddhism with the needs of the imperial government.

But there were also individuals outside of the official regulated system. They were unregistered and unsupported by the court apparatus.

The founders of two influential schools – Saichō (Tendai) and Kūkai (Shingon), had quite different origins.

Saichō was ordained as a novice at Tōdai-ji temple, in Nara, at the age of 13.

He was part of the formal Buddhist system.

Saichō seems to have become somewhat disillusioned with the institutionalised Buddhism. The established schools were powerful but they were also rigid.

At the age of 18 he left Nara to live in a hut on Mount Hiei. He wanted to devote himself to intense study and practice and he wanted to deepen his ascetic practice.

It seems that Saichō wanted more freedom to explore different ideas. He may have found the Buddhist establishment rather suffocating.

He studied the Lotus Sutra, the Heart Sutra and Tientai teachings.

In time, he became known for his efforts and scholarship and he came to the attention of Emperor Kanmu.

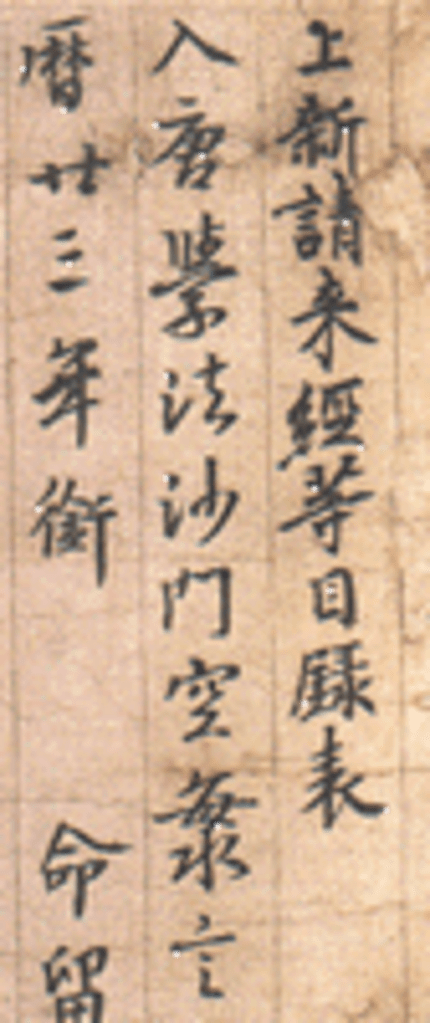

In 804 he was selected to go on a state-sponsored trip to China for more study and to bring more Buddhist teachings back to Japan.

He only spent 9 months in China but the experience would be profound for Saichō and for the course of Japanese Buddhism.

In China he studied more Tientai teachings as well as esoteric practices.

Kūkai

Kūkai, the founder of Shingon, came to Buddhism rather late.

He was initially educated for government administration.

Many of Japan’s governance ideas had been borrowed from China.

Kūkai would have studied the Chinese classics as part of his preparation for later life.

But like Saichō, Kūkai seemed dissatisfied with his studies and he turned towards religion.

Kūkai had been born in Shikoku and the island was his stomping ground.

He was drawn towards asceticism.

His environment in which he grew up was probably a very mystical one.

Pilgrimage became important to his practice.

In contrast to Saichō, Kūkai was a layman. He had not been formally ordained.

However, in 804 he took ordination and in the same year he was on his way to China on the same voyage as Saichō. This was one of those pivotal events for Japanese Buddhism.

Four ships set out for China. Saichō was on one and Kūkai was on another. Two of the ships never made it to the mainland.

It is not entirely clear how Kūkai came to be on the voyage to China.

On the face of it it does seem quite incongruous that someone so clearly outside of the Buddhist mainstream had been allowed to go.

This is one of those enduring mysteries of Kūkai’s life.

It has been speculated that he may have had some family connection to the Japanese court. While this may explain why he was allowed to go, we can’t be sure that this was the case.

Kūkai had wanted to be initiated into esoteric practices.

He brought back the Womb World Mandala – Taizōkai (胎蔵界曼荼羅) and the Diamond World Mandala – Kongōkai (金剛界曼荼羅).

These mandalas are common in both Shingon and Tendai.

Kūkai returned to Japan in 806. So we can see that Kūkai had been in China longer than Saichō but it was still a relatively short time.

Saichō returned to Japan first. The court seemed to be more open to and interested in esoteric Buddhism.

In 806 the court allowed Saichō to have 2 Tendai ordinates a year. This didn’t come into effect until 810 but this was a massive deal. It was not at all easy establish a new Buddhist school in Japan. The existing Nara schools were not esoteric. Saichō’s Tendai school represented something new and a departure from established forms.

Kūkai was not as warmly received as Saichō had been. Kūkai encountered a new Emperor – Emperor Saga. Kūkai and Saga would go on to establish a good relationship.

Saichō focused on establishing the Mt Hiei temple complex.

In China, Kūkai had received more teachings than Saichō. It seems that Saichō was aware of this and he approached Kūkai so that he could better understand what Kūkai had learnt.

The two had slightly different views on the role of esoteric teachings (mikkyo) in Buddhist practice.

Kūkai thought that mikkyo teachings should stand alone.

Saichō believed that they were important, but that they should be just one part of a whole.

This difference continues to this day and forms the basic fault line between Tendai and Shingon.

Shingon relies a lot on oral transmission.

Tendai is more textual.

Saichō passed away in 822.

Kūkai’s Shingon school would also go on to gain official recognition and begin ordinations.

One key issue for Saichō was the vows for monks. For a long time, monks in Japan had operated under the vinyana rules. Saichō had wanted monks to take bodhisattva precept vows instead. Saichō was successful in bringing about this change, but it only occurred after his death.

Saichō had a profound effect on Japanese Buddhism.

The adoption of the bodhisattva precept vows was adopted by many Buddist schools in Japan including Tendai, Shingon, Zen and Nichiren. As a result, Japanese monks often operate quite differently to Theravada monks. In Japan, monks may be married and their lives may resemble lay practitioners in many respects.

Saichō and Kūkai are interesting figures in the history of Japanese Buddhism.

Both went to China for very short periods of time. They brought esoteric Buddhism to Japan in a big way.

Kūkai seems to have been a renaissance man. He was a very accomplished calligrapher. He could read Chinese. He took on large public works projects – most famously the Manno Reservoir restoration in 821 CE. He seemed to be a capable leader a capable manager of people.

Leave a comment